As the data universe grows into zettabytes, and as venture-backed startups crowd into the market, how can tech professionals keep up with the myriad choices of database management systems?

There’s a database for that.

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have compiled the “Database of Databases,” a searchable compendium of nearly 800 different database management systems that have been developed over the past 50 years.

Looking for a MySQL-compatible database? The Database of Databases lists 27 of them. A PostgreSQL-compatible database? There are 25 to choose from.

The Database of Databases may be the world’s most comprehensive knowledge base of DBMSs. The website identifies category leaders by country of origin, license type, programming language, and other criteria. As such, it’s a valuable resource for developers, DBAs, entrepreneurs, CTOs, students, and anyone who wants to dig into the inner workings of databases, from system and storage architecture to query interfaces.

‘Databases Don’t Die’

Carnegie Mellon associate professor Andy Pavlo created the Database of Databases to support his own research and to help CMU students grasp the real-world implementations of database techniques and algorithms. “I just felt it would be helpful to have a catalog to keep track of everything that was out there,” says Pavlo, who researches and teaches “databaseology” in CMU’s Computer Science Department.

The Database of Databases identifies hundreds of commercial and open-source databases, including industry-leading cloud database platforms from IBM, AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft, Oracle, and others. In addition, there are academic databases and a small category of “hobby” databases, such as PickleDB, a lightweight, key-value DBMS written in Python.

The website identifies the newest databases, some of which you may not have heard of, such as BonsaiDB, a Rust database by Khonsu Labs, and CogDB, a micrograph database for Python applications.

At the same time, the Database of Databases is noteworthy, and potentially very useful, at the other end of the spectrum. It includes pre-Internet databases developed in the 1960s and ’70s, such as Rocket Software’s Model 204 (circa 1965) and IBM’s IMS (1968).

That could prove useful to the many organizations that are challenged to manage years-old data stored in legacy databases. “Databases don’t die,” says Pavlo.

In some cases, vendors continue to provide maintenance paths for their decades-old database platforms. For example, Software AG has outlined a cloud modernization plan for Adabas, originally developed in 1971, that stretches to 2050. That would extend the database’s lifespan to nearly 80 years.

Relational Model’s Staying Power

It’s remarkable that nearly 800 different databases have been developed since IBM computer scientist Ted Codd introduced the relational database model—where structured data is organized in rows and columns—in 1970. Pavlo explains that database systems have emerged in waves, driven by mainframes, the Internet, open-source, and now cloud.

Today, venture-backed startups are fueling a new generation of cloud-native databases for modern use cases such as analytics, gaming, social search, data distribution, and other digital business imperatives.

During this phase, NoSQL and special-purpose databases—i.e. time series, graph, vector, and others—have risen in popularity. Even so, Pavlo says relational databases have staying power. “I think most workloads and applications are best served in a relational database,” he says.

Given the long history of relational databases, it’s not surprising that they are well represented in Carnegie Mellon’s all-inclusive list—there are 259 entries for relational databases.

That’s both good news (because there are so many choices) and bad news (because there are potentially too many choices). But the Database of Databases website makes it easy to narrow that down with its filtering menu. For example, if you search for commercial relational databases that are derived from Postgres, there are nine results, which is much more manageable than wading through the complete list of 259 relational databases.

No End in Sight

For database aficionados like myself, there are many gems to be found in this pile of hundreds of database systems. For example, there’s Espresso, a MySQL-compatible DBMS used internally by LinkedIn.

And the number of DBMSs tracked by Carnegie Mellon’s Database Group just keeps growing as new platforms emerge, while at the same time those earlier generations continue to run on back-office servers.

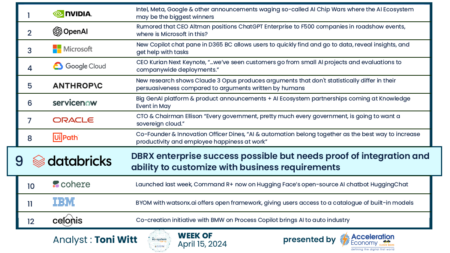

There’s a tremendous amount of innovation and new development underway in the database market, as relative newcomers such as Cockroach Labs, Couchbase, Redis, SingleStore, and Yugabyte take on bigger, more established database providers, including AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft, and Oracle. Check out the Cloud Database Battleground to see how the new database platforms compare.

As I reported on Acceleration Economy, 10 database startups pulled in $2.9 billion in funding last year. But Pavlo does not expect development of entirely new DBMSs to continue at today’s pace. “I would say that long term this is not sustainable,” he says.

Pavlo recently launched his own startup, OtterTune, which uses machine learning to automatically tune DBMSs (in particular, MySQL and Postgres on Amazon RDS). He’s also working on a longer-term project to develop autonomous database technology.

Because with so much data and so many databases out there, DBAs need all the help they can get with hands-on management. “At the end of the day, it isn’t just about better performance and lower costs,” explains Pavlo. “We want to sell peace of mind.”